Explaining AI Explainability: The Current Reality for Businesses

In our first post, we examined why "AI as magic" may be fine for casual applications, but is problematic for high risk AI applications, where AI outputs can and do lead to longer prison sentences, health costs being refused by an insurance company, traffic deaths and many other outcomes that put health, safety or fundamental rights at risk.

We also unpacked what kind of why explanation we would need from AI, and saw that they split into five broad categories of explanation purposes:

"Why" to understand and debug the world

"Why" to feel reassured

"Why" to challenge a decision

"Why" for informed consent

"Why" to assign liability

In this post, we look at how close existing implementations are to achieving these goals, and also survey some current research trying to push those boundaries further.

Before doing so, however, let's return to our Sherlock Explanation of our previous post:

Sherlock Explanation: A seemingly magical AI output that, when provided to an affected stakeholder, makes the outcome "simple enough when you explain it."

We can already start to see by thinking more about the above 5 "why"s that some of these "why"s are more relevant to certain stakeholders than others, e.g.

an AI developer or an AI risk manager might be particularly interested in the first "why" about understanding and debugging their AI model,

an end-user or product manager of an AI service might be most interested in feeling reassured about the AI outcome, the second "why",

an end-user or regulator might be especially focused on challenging an AI output, the third "why",

a doctor following an AI diagnosis as well as the affected patient are likely most concerned with the fourth "why" of informed consent

a victim of an AI outcome and the judge as well as jury responsible for deciding whether the AI outcome was at fault would likely be focused on the final "why" of assigning liability.

We'll follow the research papers and in identifying five stakeholder personas to guide us through understanding and applying AI explainability. For each of these personas, there are typical desiderata, meaning desired essential goals.

Users: People that use the AI system. For example, medical doctors and customer support agents. Common desiderata are transparency and trust.

Developers: People who design and build AI systems. Common desiderata are model validation and debuggability.

Affected Parties: People who are affected by the (decisions of) the AI system. For example, patients and loan applicants. Common desiderata are fairness and redress.

Deployers: People that decide where to employ AI systems. For example, medical directors or chief customer officers. Common desiderata are business value and legal risk management.

Regulators and judges: People that stipulate and apply the legal and ethical norms for the use of AI systems. Common desiderata are compliance and accountability.

General vs specific-case explanations

There's one final important distinction before we consider the state-of-the-art for explainable AI, and that is whether the explanation is given for one specific case or for the average case.* In the literature, this distinction goes by other names, e.g. global ("general") vs local ("specific-case").

* "Average" here is not completely technically accurate, but it's close to how.

The state of academic research on explainable AI

For a business, hearing that some topic relevant to your company is an "active field of research" could sound exciting, as this means that top university and likely industry talent is working in the area. It should, however, raise alarm bells unless your company's value is specifically to carry out this research. Why alarm bells? Let's consider some areas of technology that are not hot areas of active research: manufacturing glass, building bridges, reliable computer data storage under ordinary conditions. These topics were active research areas many years ago, but now are so well understood and so reliable that research is focused on marginal (if still exciting to some) improvements. If a technology field is a field of active research, like explainable AI, that is generally because our current knowledge is too poor for it to be safely adopted by industry. These open questions and deficiencies of the status quo for real (including business) usage are what make for interesting research. What's interesting for researchers is precisely what can cause unreliable, faulty business operations. That is, until this research reaches a mature enough state to no longer be a hot, active topic.

To help make this review concrete, let's take one concrete example that is considered under the EU's AI act as high risk, meaning it is subject to regulation measure, including model transparency requirements (though whether explainability is required is a subject of debate).

Running example: an automated scoring model for private health insurance

If you apply for private health insurance (and maybe even public health insurance), you will likely be asked to fill in personal data including

age

profession

medical history

as well as other data points. Under medical history, you may be asked questions about high blood pressure (yes or no), epilepsy (yes or no) and existing heart condition (yes or no), to name just 3.

Based on your answers to these and other questions, the health insurance company will calculate a risk score that is supposed to capture how likely it is for you to incur a small amount of health costs ("claims") over your life time (low score) vs a large amount of health costs (high score).

Considering potential answers to these questions one-by-one, it's not too hard to develop an intuition (and challenge) what these scores should be, for example,

Age: lower age -> lower score, higher age -> higher score (e.g., in German private health insurance, the yearly costs generally go up year by year precisely because of this logic)

Profession: educational job -> lower score, top-level business executive -> higher score, as top executives are more prone to heart-attacks (e.g. a friend of had his insurance costs increase after a promotion to top management)

Medical history: low or average blood pressure -> lower score, high blood pressure -> higher score, as blood pressure is factor in heart disease.

But what happens if we consider these inputs (or "features") to the insurance scoring engine in combination?

If you are a teacher with epilepsy, then your health risk might be minor, leading to a low risk score and acceptance into the private health insurance pool. If, however, you are a construction worker with epilepsy, your risk is higher, leading to a high risk score and refusal of insurance (in the United States, at least, people with epilepsy may not be kept from construction work).

Similarly, having only high blood pressure but no heart disease might lead to a medium score, while having both could result in a high score, and rejection of health insurance.

You can also imagine higher level combinations on not only pairs of inputs, but interactions among three or more. And when you start doing that (and maybe suffering from a headache trying to come up with and keep track of all of these combinations), you start to realize why people turn to seemingly "magical" AI models for tasks like risk scoring.

This will be our running example, but let's briefly consider the AI that's getting the most attention and money: generative AI with deep neural networks, e.g. large language models. In our example of private health insurance, the inputs were number like age, categories like profession with a fixed number of possibilities, and yes / no questions about medical history. The output is a single number, a risk score for predicted health costs.

Sidebar:

With text-based GenAI, e.g. large language models, the inputs and outputs are free text. How many combinations of free text and their influence on the free text output should we consider? The way to make this question precise takes us too far away from the current topic, but just to give you some numbers to think about, first, the input has to be translated into an AI-oriented vocabulary called "tokens," of which GTP-4o has approximately 200k, which is not far off from the estimate of in-use words in the English language, though a token can be both a subword, like , as well as a "super" word, like "New York".

For example, using GPT-4o's token algorithm ("tokenizer"), the following python code

import tiktoken

encoding = tiktoken.get_encoding("o200k_base")

text = 'I heart explainable AI!'

tokens = encoding.encode(text)

tokens_back_to_byte_text = [encoding.decode_single_token_bytes(token) for token in tokens]

print("Text to be converted into tokens:\n\n", ' ', text)

print("\nTokens converted back to (byte) text:\n\n", ' ', tokens_back_to_byte_text)

shows how the four-word text

I heart explainable AI!is translated into a "token" vocabulary with six elements, with the wordexplainablesplit into two tokens,explainandable, and the exclamation point at the end getting its own token as well:

Text to be converted into tokens:

I heart explainable AI!

Tokens converted back to (byte) text:

[b'I', b' heart', b' explain', b'able', b' AI', b'!']

Each of these tokens is then converted into a LARGE series of numbers called a "vector." OpenAI's models use 1536 such numbers per token (so a vector of length 1536). Back of the envelope calculations were never my forte (part of why I switched from physics to mathematics) but we'll wrap this technical detour with a relatively straightforward comparison to the one-by-one effect of AI inputs to its output. In the health insurance case, the number of distinct input values (ignoring combinations) is something like 78 for age values, 200 for occupation values, and about 100 for health conditions, so let's round up to approximately 400 individual input values for which we could consider how each value individually affects the health insurance risk score.

The input size of the AI model vocabulary input is about 200k tokens, each of which is assigned to 1.5k numbers (a vector of length 1536). So that's about 300 million inputs to consider. If we move to considering the effects of combinations of input values, both numbers explode, with the large language model exploding even biggerer (ungrammatical word use intentional for emphasis).

(End of the sidebar)

Let's now begin our review of state-of-the-art explainable AI with a few topics that aren't hot research areas (apologies to people working in these fields---I will be happy to correct inaccuracies and promote your research in revised versions).

Interpretable AI algorithms

The most manageable AI model outputs to explain come from so-called interpretable models, meaning roughly that a Sherlock explanation is possible due to the nature of the model. A stakeholder (e.g. developer, end-user, regulator, auditor) may not have come up with the AI model themselves, but once the model's actual workings are explained, then it is "simple enough" to understand the output, and therefore trust it or challenge it.

A common example of an interpretable model is a linear one, for which 1. all interactions among inputs are ignored and 2. each change in input has a direct and transparent effect on the output.

If we had a linear risk scoring model for health insurance, then you might have that every additional year of age makes an applicant's score increase by a fixed amount, e.g. 0.05, so that a 20 year old applicant would have a contribution of 20 x 0.05 = +1 to their risk score, whereas a 100 year old's risk score would have a contribution of 100 x 0.05 = 5 to their score.

Likewise, with a linear model, having high blood pressure might contribute 2, while no high blood pressure would contribute 0 to the score. If we translate the property of having a medical condition into the number 1, and not having it into the number 0, then we can write the contribution of blood pressure as an indicator value (1 for has it, 0 for doesn't have it) times a factor value (size of the score contribution).

Then the contribution from high blood pressure looks like

contribution=indicator×factor,contribution=indicator×factor,

or 1 x 2 = 2 contribution if high blood pressure, or 0 x 2 = 0 if no high blood pressure.

With such a linear model, it is impossible to have the final risk score depend on interactions of inputs. So even if medical research indicates that a person having high blood pressure and a heart condition leads to much higher estimated medical costs than different people having high blood pressure or a heart condition separately, the model cannot reflect this interaction among inputs.

At this level of detail, what we've described so far as a linear model are nearly identical to a score-card model. The commonality is that input data contribute to the final risk score by a multiplication of an input datapoint-specific factor with the input value, and then all of these individual multiplication terms are added to to get the final risk score. Score-card models have been used in the past (and likely still today) for automated bank loan decisions.

A key difference between linear models and score cards is how these factor values are determined. In score card models, the factor values are determined by expert judgement, which can be influenced by a statistical analysis of historical data, but need not be.

In linear models, however, these factor values are determined by training the model with historical data. There are plenty of other blog posts, articles and books out there that can give you a good introduction to what's meant by training a model with historical data, so here we just give a nutshell version. First, you need curated historical data. By "curated" I want to emphasize that there's always a series of decisions and also likely filtering or other transformations to come up with historical data suitable for model training. In contrast to the score card expert-judgment approach for determining factor values, with model training, the curated training historical data is used to statistically determine the "best" values. Best for what? you might be wondering. Determining what "best" means is another key area where human expertise and decisions play a critical role. In our health insurance example, "best" might mean the factor values that, when multiplied by historical values, give the closest approximation to what a customer with those input values will incur in health costs over an average year.

While these automated linear or score-card models maybe have been billed as artificial intelligence when they were first introduced, they are generally not considered as AI today. Nevertheless, the linear models that are fitted to curated historical data share with more advanced models two key dependencies for their performance and failure risk: they are critically dependent on 1. the curated historical data used to train them, and 2. the choice of "best" fit to the data.

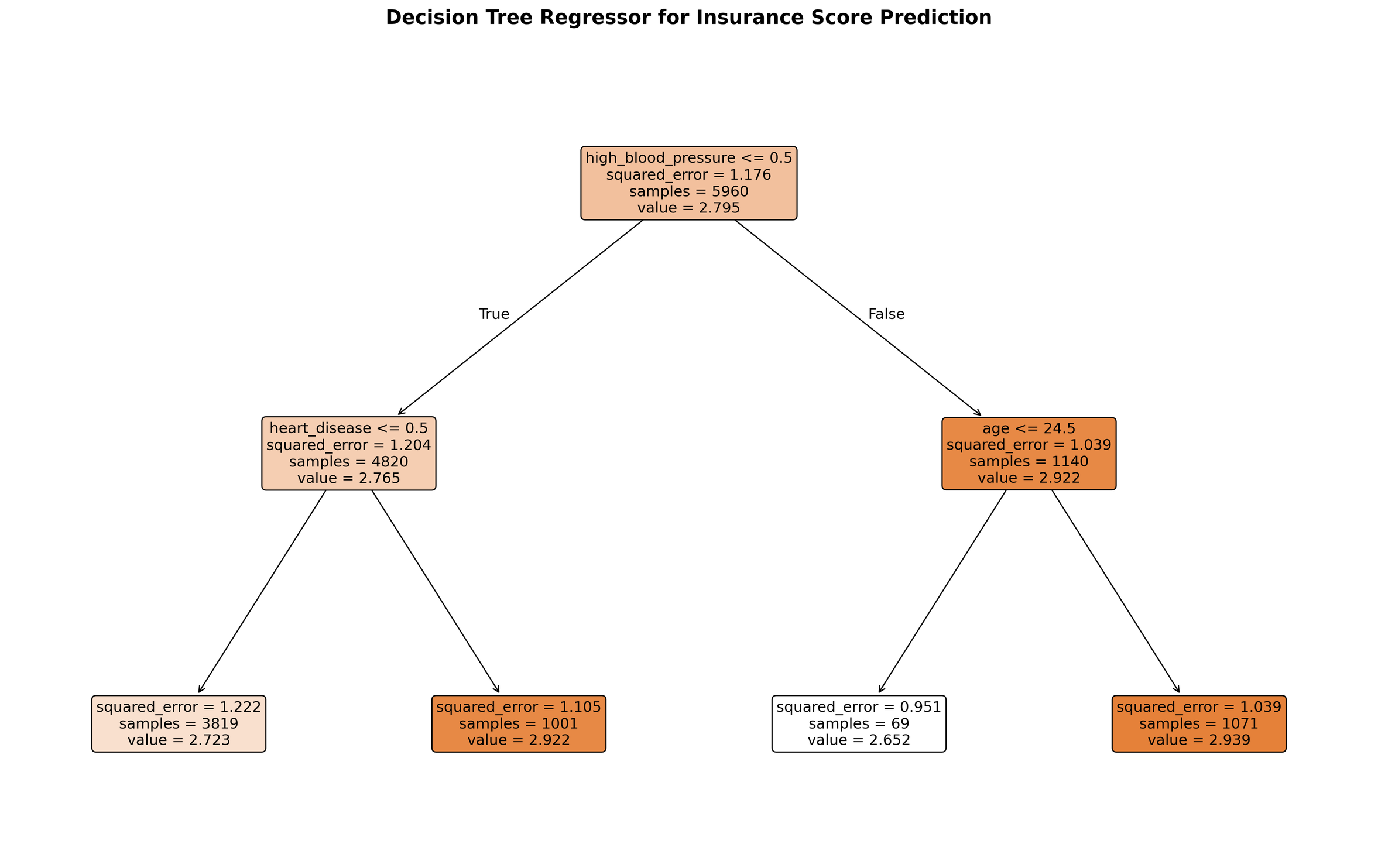

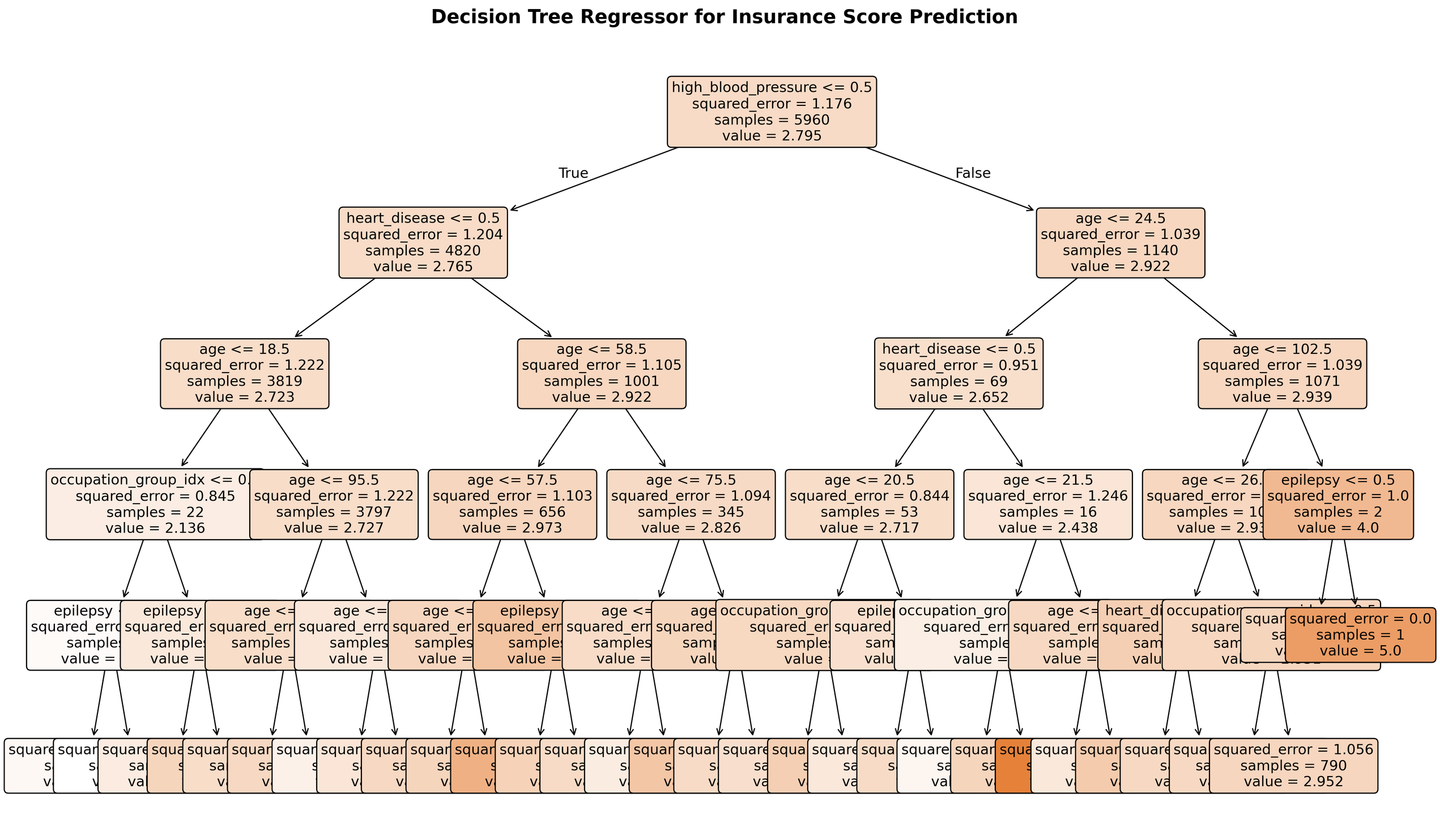

A second model commonly deemed interpretable is decision trees. Unlike the linear models above, decision trees can take into account interactions among input data per applicant. Like the linear models, in contrast to score card models, decision trees are also fitted to curated historical data.

The basic idea of a decision tree is to determine how to split the data values into subgroups having similar risk scores, and then take the average score per smallest subgroup as the predicted risk score for that group. The model is called a "tree" because first one of the data inputs is chosen for the top split into "branches", e.g. if the high_blood_pressure value is 0 or 1, then within each of the high and low blood pressure groups, a further split is performed until the splitting process stops, resulting in the final, most granular subgroups, called "leaves."

A decision tree like the above is considered interpretable since we can in principle see exactly how the final model will function. For each individual health insurance applicant, we can trace how their responses about age, occupation and medical history work their way through the decision tree until arriving at the model's answer for their risk score.

Do interpretable decision trees also lead to Sherlock explanations? Can any stakeholder be presented a decision tree and agree with or challenge its outputs because the explanation is "simple enough"? For small decision trees like the one above, this may be possible. As the number of inputs increases, however, it is a stretch to consider the explanation of a decision tree "simple enough." What if our insurance claim model considered a more realistic 400 different input data values per applicant, rather than the fewer than 10 values used in the above example. Even if we stay with a small number of different input values to be sorted into the smallest subpopulations, or "leaves," if we allow more complicated trees, are the inner workings of a decision tree still "simple enough"? Below is a visualization of a decision tree for risk scoring in which we've allowed more granular subgroups.

For high-stakes applications, even interpretable models can be sufficiently complicated that Sherlock explanations are not possible. We'll consider in depth in our final blog post on explainable AI in regulation how both businesses and regulators can deal with this challenge.

Key takeaways

Interpretable AI / statistical models can provide Sherlock explanations if the variety of input data fields is small, and the AI / statistical model is also kept small.

Nevertheless, answering why? to challenge a decision or assign liability still requires statistically justifying model parameters with respect to historical data used to train it, thus making Sherlock answers impossible for personas without statistics training, such as users, affected parties, many deployers and many regulators or auditors.

For input data with high variety or models with low complexity (or both), Sherlock answers are often possible for developers and deployers for the why? questions of debugging the model, and, with some training, for non-technical stakeholders to feel reassured about outputs, but not for other purposes.

General (aka global) explainable AI techniques

In the previous section, we say how interpretable AI models make it possible in theory to get a Sherlock explanation due to the relatively simple nature of the model. In practice, however, even these algorithmically simple models can be difficult to trace from input to output when the size of the model grows.

What's difficult for an individual input and its corresponding AI model output can sometimes be more manageable on the population level. Again, Sherlock Holmes is a useful resource here. When considering human behavior, he muses that while predicting what a single human will do in a given situation may be impossible (input=human + situation, output=what the person does), when we average over human behavior, the situation is much different. Holmes says in "The Sign of Four" (actually quoting a non-fictional person, Winwood Reade),

[W]hile the individual man is an insoluble puzzle, in the aggregate he becomes a mathematical certainty. You can, for example, never foretell what any one man will do, but you can say with precision what an average number will be up to.

This is roughly the approach taking by global explainable AI techniques by giving insight into how a given AI model behaves by averaging (or otherwise aggregating) over the effects a population data, rather than single data points, has on its behavior.

The main category of these techniques goes under the heading of "feature importance," where a "feature" is either an input data element or some transformation of an input data element, often combined with other input data elements.

For example, in our running life-insurance scoring model, age could be a direct model input, in which case there is no difference the input and its corresponding feature to be fed into the model are identical. More likely, however, is that the raw data does not contain ages, as these are dependent on when the calculation is being run (each day you get older). In this case, the raw input data field is likely date of birth, e.g. "January 1, 1970", and the age is calculated by taking the number of years since the data of birth. In this case age is a feature derived from raw date-of-birth data. Even more likely is that it's better for modeling purposes to group ages into categories, perhaps something simple like mapping each age into a decades-old feature or something more advanced like determining age-groups dynamically.

Perhaps the most straightforward global feature importance is correlation between feature values and the (correct) target values. In our example, if we wanted to determine how important age was for determining the scoring model outputs, the correlation between these sets of values gives us some insight. Note that correlation only makes sense for populations of values, not individual ones, hence the "global" categorization.

Whether its a simple, limited technique such as correlation between feature values and correct output values, or more advanced techniques, the key characteristic of global techniques is that they always involve averaging (or some other aggregation) over a population of the data.

In particular,

Global explainable AI techniques give insight about populations of data populations which may, or may not, help understand individual cases.

Can global explainable AI help us arrive at Sherlock explanations?

For those of us having AI as a day job, the explanations are (after some study) often "simple enough." They furthermore help AI developers and deployers understand and debug the AI world and can sometimes, if the features are simple enough to understand, even enable end-users of AI system to feel reassured.

The same may even hold for data-science savvy regulators or auditors. Beyond that, for the other combinations of why's and personas, global explainable AI techniques can't really offer Sherlock explanations.

Now that we've covered global explainable AI techniques, we turn to its local counterpart. To ease readers into the subject, we do so by means of a fictitious medical device that demonstrates in a more familiar medical context both what local explainable AI tries to accomplish, and why achieving these goals is difficult.

Key takeaways

General (aka global) explainable AI techniques are most useful for developers and deployers for developing and debugging AI models.

General explainable AI techniques can be useful for non-technical personas (users, affected parties) for feeling reassured or informed consent, though can hardly deliver Sherlock explanations due to statistical knowledge required for the explanation to seem "simple enough."

General explainable AI techniques are, by construction, unsuitable for challenging a decision or assigning liability, as they focus on AI behavior on populations, not individual cases.

Introducing the OmniProbe: a made-up medical analogy for local explainable AI

The inspiration for the fictional OmniProbe we'll consider to help understand local explainable AI comes from a Slovenian medical device company called MESI, where a few friends work. Their offering is a suite of portable medical devices whose outputs feed into an integrated data platform that medical professionals then access through a tablet device or desktop application. For OmniProbe, let's take MESI's products a few fictional steps further, and imagine that OmniProbe is a single device that can be used to detect nearly all medical conditions, and presents diagnosis in a faithful, understandable form.

Main features of the fictional OmniProbe device

a single device that

can be used to detect nearly all medical conditions, and

presents diagnoses in a factually correct ("faithful"), understandable form.

Note that 1. and 2. might not be that impressive, as long as you gave up on the device being small, as you could imagine engineering an uberdevice that has inside of it all other medical devices, only one of which is called depending on the part of the body being examined. But add in condition 3, and you have a serious challenge, as medical devices have very different outputs: black-and-white images from an X-ray of some body part, a wave form graph from an electrocardiograph (ECG) of heart functioning, two numbers from a blood pressure machine (diastolic and systolic pressure), one number from a thermometer (temperature), two different numbers for a pulse oximeter (pulse and blood oxygen saturation), etc..

The fix for feature 3. of our OmniProbe is more or less how local explainable AI works: for each of the original medical devices, and for each individual patient's body-part being examined, the OmniProbe somehow approximates the original device functionality to give a universal, factually correct, and understandable diagnosis.

Wouldn't this be magical?

You can perhaps already see both why such a device (medical or machine learning) would be extremely useful, and why it would be extremely challenging to build. Staying with the medical example, doctors trained to examine X-rays and MRI scans require 13 years of education before they may practice independently in the United States, 14 years a full-fledged cardiologist, and 12-14 years for neurology. European medical training typically takes 2-4 years fewer, as the initial undergraduate and medical degree programs are combined.

For simpler measurements like blood pressure, it is reasonable (and common) to have Sherlock explanations, where this device that pumps air into a cuff around your arm to somehow predict your risk of heart disease seems "simple enough" once a patient is explained that the higher number measures how hard your heart has to work to pump blood under exertion, and the lower one at rest. Sure, if your heart has to work harder than average, then it's understandable that it will be at risk. But what about a Sherlock explanation for medical diagnoses whose experts train theory and practice for over a decade?

Carrying over to AI, the analogue of a temperature or blood pressure measurement is an interpretable AI model introduced above, while the analogue of a heart or brain diagnostic device is a black-box model with thousands to billions of parameters such as the deep neural networks powering large language models. Even without going all the way to deep neural networks with billions of parameters, our discussion of how inputs can interact in our running example of a private health insurance score gives reason to be skeptical about an OmniProbe device that promises a Sherlock explanation. If we only consider the inputs independently, which is often the case in interpretable models, then a "that's simple enough" explanation seems reasonable. Once we consider interactions among inputs (occupation interacting with age interacting with one or more medical conditions), then it seems less likely that an explanation that's factually correct to how the insurance scoring model works AND is "simple enough" for stakeholders is possible. This dilemma is fundamental for explainable AI, as it's the often successful handling of these interactions among many inputs that makes black-box AI models attractive in the first place.

Explaining case-specific, local explainable AI

Now we come to the latest, best hope for Sherlock explanations for all why? forms and all personas. Simple interpretable models for input data with few variations can give Sherlock explanations, though not without statistical training and analyses for non-technical personas like users, affected parties and regulators (or judges, compliance officers or auditors).

Turning to more complicated interpretable models or non-interpretable, so-called "black-box" models, we saw that general (or global) explainable AI techniques can only provide Sherlock, "simple enough" explanations for developers and possibly deployers for developing and debugging models, but are unsuited for other personas and other why? questions. Furthermore, general explainable AI techniques are, by design unsuited for challenging individual outcomes, as they work only on a population of inputs, not individual ones.

Case-specific explainable AI attempts to carry over the "simple enough" nature of interpretable AI models to individual cases of black-box models.

The central idea of case-specific (or local) explainable AI is to use an interpretable AI model to approximate a black-box AI model for a specific case.

The most popular and widely researched case-specific explainable AI techniques, such as LIME and SHAP to be introduced shortly, go even further, just as our fictitious OmniProbe does, as they can be applied to almost any black-box model using (nearly) the same technique.

Now it should be clear why two papers that introduced OmniProbe like capabilities garnered so much academic and industry interest (note, however, that Erik Štrumbelj's PhD thesis research was the first to discover the connection between collaborative game theory and explainable AI).

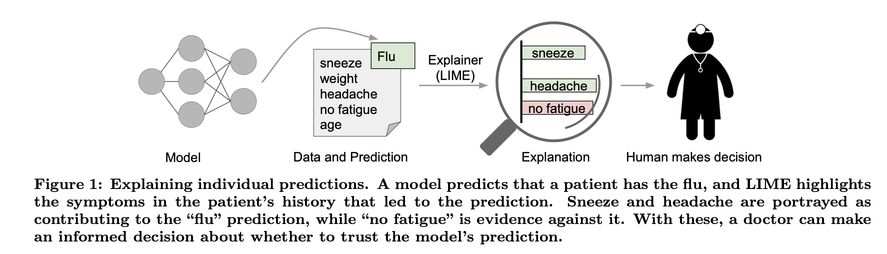

In the earlier of these two papers, “Why Should I Trust You?” Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier', the authors develop a technique that produces feature importance insight (as described above in our section about general explainable AI) for specific inputs and outputs, thus seemingly overcoming limitation of general techniques to only population-level, averaged insights.

In the below figure, the authors give an example how a black-box medical diagnosis AI model can be "explained" for an individual prediction by showing which input features are most important and least important in determining the output.

In the above example, the why? question LIME purports to ask is informed consent, and the stakeholders a doctor (user) and their patient (affected party).

They call their technique "Locally Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations," or LIME for short.

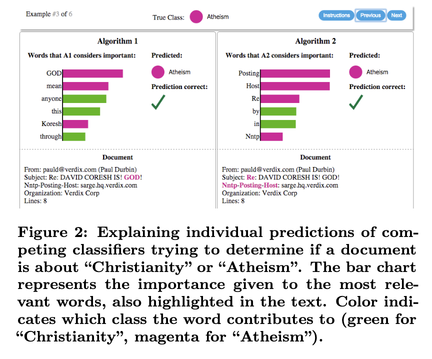

If instead we have a language model, like the GenAI large language models you have probably used in chatbots and as described in our Technical Sidebar above, then the author's LIME technique can give, for a given language-based task, the key words that contributed to the outcome. In the figure below, the language task is to classify input text as being about "Christianity" or "Atheism." The LIME technique flags individual words the most contributed to the output of "Christianity" or "Atheism."

In this example, the why? question is about understanding and debugging AI models, and the relevant stakeholder is a developer using the LIME explanations as part of deciding if Algorithm 1 (i.e. AI model 1) on the left side, or Algorithm 2 on the right side is better for their AI development work.

The second paper, "A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions", shows how the LIME technique can be unified along with five other explainable AI techniques into a single technique that they call "SHAP," a somewhat tortured acronym for "SHapley Additive exPlanations." Furthermore, the authors show that their SHAP technique uniquely satisfied certain criteria we would want out of a Sherlock explanation. We only highlight only one of these criteria here, called local accuracy.

As noted above, these case-specific explainable AI techniques, like our fictional OmniProbe, is not an exact replica of the original, black-box AI model, but is a simpler approximation for that model at the specific data-input, or case. Local accuracy is precisely this criterion: for each specific case (aka input data), the simpler model approximation should be almost identical to the original, black-box model for a specific case and all other cases "similar" to it (or "close", as can be made mathematically precise and is indicated by the word "local" for this family of techniques).

A consequence is that different approximate, local models (also called "proxy models") are needed for different cases. This downside of having to come up with a large number of approximate, interpretable models is supposed to be compensated by the benefits of having accurate, interpretable explanations.

Have we found with case-specific explainable AI techniques like LIME and SHAP our tool for Sherlock explanations even for extremely complicated black-box AI?

Here's the case for saying "yes":

Local explainable AI techniques use so-called interpretable AI models as the proxy-model explainers

Local explainable AI techniques can often accurately approximate the black-box model at a specific-case, so even though the proxy model isn't as powerful over all cases (or input data), it can be a faithful approximation for an individual case.

We'll divide the reasons to doubt case-specific explainable AI has realized our business vision into a few subcategories:

are the explanations truly "simple enough" for different persona?

can we trust the approximation?

are the explanations truly useful?

Are use-case specific explanations simple enough?

We've laid the ground work already in our discussion of interpretable AI to see that the answer to this question is generally "no" except for technical stakeholders using the explanations for debugging their models or other non-technical stakeholders for the purpose of feeling reassured.

Can we trust the local approximation of black-box models?

This reason for concern is more technical, but hopefully appreciable also for non-technical readers as well. We are considering AI models because they often give powerfully accurate outputs from complicated input data gathered from complex real-world phenomena, like a person with a medical history, occupation, hobbies (some dangerous, some not) who wants to get private health insurance. We often forget how incredibly complicated that reality is compared to what's studied in most physical sciences.

Businesses are interested in black-box AI models because they can give very accurate approximations to very complicated real-world situations. Now on top of these black-box models, case-specific explainable AI introduces a new AI model to approximate the black box model, one for each case of interest. This results in a large number of new proxy models that also have to be trusted and checked for accuracy. Do we need a third set of AI models for this task?

Such questions aren't just nit-picking or philosophizing. In a 2024 paper, "Post-hoc vs ante-hoc explanations: xAI design guidelines for data scientists", the authors highlight the difficulty of knowing which explainable AI technique to apply for a given task. Another late 2024 paper, "An Overview of the Empirical Evaluation of Explainable AI (XAI): A Comprehensive Guideline for User-Centered Evaluation in XAI" highlights the problem of rigorous evaluations of local explainable AI techniques as an active, important research area.

Recall our warning from the first post on explainable AI. When a topic is an exciting, active research area for academics, that's a good sign that it is not reliable enough for widespread use in industry.

Are use-case specific explanations really useful?

So far, the most promising uses of explainable AI techniques have been for technical stakeholders performing technical why tasks, like developing or debugging AI models. Much of the literature claims that these explanations should also be useful for other stakeholders. If true, then business should be able to get reassurance from user-studies that empirically demonstrate how well explainable AI techniques can be used in life-like situations by a range of stakeholders.

The judgement of 2025 research by Erik Štrumbelj and his group demonstrates that evidence for real-world usefulness of explainable AI for different stakeholders is severely lacking. In Position: Explainable AI Cannot Advance Without Better User Studies, they demonstrate via a systematic literature review that practice-near user studies are largely non-existent, with most research focusing instead on easier to implement non-user studies or weak proxy studies, e.g. subjective responses about utility of explanations or crowd-sourced proxy tasks.

Takeaways

Case-specific, or "local," explainable AI offers the best current hope for Sherlock explanations of black-box AI.

Current approaches can be useful for AI developers and deployers for why questions about debugging and also potentially for users or affected parties for offering reassurance.

The reliance on so-called interpretable AI models and feature importance runs up against the concerns we raised in the section Interpretable AI models and General explainable AI.

The use of proxy models for local explanations opens up a new, active research area of rigorously evaluating local explainable AI techniques.

Current empirical evidence is poor about the actual usefulness of explainable AI techniques in real-world-like situations

Should businesses trust explainable AI?

First, the bad news. Our lofty visions of businesses benefitting from the power and often better-than-human accuracy of black-box AI models, like Large Language Models, together with "simple enough" Sherlock explanations to enable all stakeholders for all why questions can't be met by the current state of explainable AI research and practice.

If a vendor (or even internal AI team) is telling you that their AI solution gives you both amazing performance and complete explainability, then you should scrutinize the offer very carefully before allocating budget or resources.

There is some good news, however. Even if state-of-the-art explainable AI doesn't meet all of our needs today, the loftiness of our visions means that many researchers and AI-focused companies are investing into achieving more and more of this vision.

Second, some question the often-claimed tradeoff between model complexity and accuracy, namely, that only the most complicated, black-box models can achieve required accuracy for business applications. Cynthia Rudin of Duke University is one of the best-known critics of what she calls a false tradeoff (see her much-cited paper "Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead"). My experience and that of others I've worked with is often that the more complicated AI models that seem best on historical data often underperform compared to simpler, more interpretable AI models in real applications.

And finally, business AI applications don't always require Sherlock explanations for all possible why questions and all possible stakeholders. Rudin's paper focuses on high-risk applications. For low risk applications of AI, it's often a worthwhile tradeoff to deploy a black-box model for which Sherlock explanations aren't available because the automation or better performance benefits far outweigh the cost of errors.

For high-risk AI applications, however, the cost of errors can be high, often unacceptably high. Recent regulation of AI in Europe, Japan, China and Brazil focuses largely on such high-risk application areas. In our final post in this series, we'll examine how much of this regulation applies to explainable AI, and what your businesses needs to do to be prepared.

Article Series "Explaining AI Explainability"

- Explaining AI Explainability: Vision, Reality and Regulation

- Explaining AI Explainability: The Current Reality for Businesses